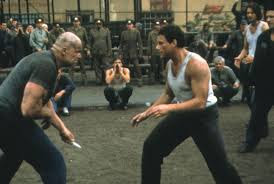

10. "In Hell" (2003) - I've only seen a few Ringo Lam films.... something I'm hoping to change in the new year. With one of his many Jean Claude Van Damme collaborations, "In Hell" is a good start to the auteur's canon. A prison drama that not only trots out all the brutal genre tropes but manages to weave in some poetic asides about the nature of confinement and how the system brutalizes man's humanity, "In Hell" is essentially a fight club behind bars. When everyman Kyle (Van Damme) finds himself behind bars in a Russian prison, he goes through a series of personal revelations that range from absolution of self in "the hole" to a martyr that kick starts a revolt among the inmates. The film

also finds time to play up some hokey mysticism and a voice over from Lawrence Taylor (yes, that one) that adds a touch of philosophical depth to the mayhem. I had so much fun with this one.

9. "The Makioka Sisters" (1983) - Kon Ichikawa's "The Makioka Sisters" trades on alot of the same

sentiments that made Ozu such a beloved figure in international cinema.

It's a film that concerns itself primarily with the task of finding

suitable husbands for two of the 4 titular sisters... something that

drove so many of Ozu's efforts about the nuclear family and its

important formation. And while Ozu deserves his place in the echelon,

Ichikawa has worked a bit more in the margins and toggled through all

types of genre. And while no one is going to accuse him of stepping on

Ozu's toes in subject matter, in my opinion, "The Makioka Sisters" is

better than anything ever produced by him. Released in 1983, "The Makioka Sisters" (only 1 of his 93 films spanning

from the late 30's until 2006) also uses color brilliantly. From a face

bathed in red light inside a photography production room to the sickly

green hue of a corner bar, it's a film that sees a purpose in each

designation. Of course, there's the obligatory cherry blossoms as well.

In a scene that bookends the opening and closing images, time has passed

and life has been altered. But luckily, there's no great sadness. No

one has died and the world is still spinning, although Yukiko and Taeko

are at vastly different paths in their lives. And even though some

melancholy has settled, "The Makioka Sisters" proves that even minor

shifts can have tremendous impact.

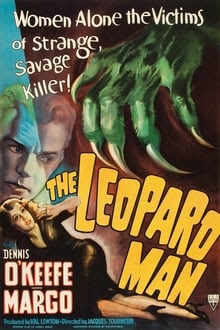

8. The Leopard Man (1943) - I'm not sure what I expected from the Val Lewton factory produced "The

Leopard Man". I mean, all of their output swerves in interesting, digressive ways but this film is something different (and magnificent). After the aforementioned leopard wildly escapes towards

the beginning and claws the hand of a waiter on its torrid exit, I

thought maybe we'd get an infected man terror tale. Then the wild animal

corners and hunts a young girl in a scene that ranks as one of the most

heartbreaking demises in cinema. Then more and more people turn up dead

and it appears there's a serial killer on the loose. What's so good

about Jacques Tourneur's film is the simple exploration of fear and how it instinctively seems to metastasize during certain periods. Much

like war-torn Berlin and serial killer Paul Ogorzow's litter of corpses that went under speculated simply because it took place during the Nazi regime of disappearances, history often

reveals that evil is born and enabled by a political shroud of terror. In "The Leopard Man:, the town

experiencing the fear of a loose beast soon turns on itself and gives in

to its primal urges, turning even the most lucid figures into Jekyll

and Hyde-like depositors of destruction. "The Leopard Man" is pure

trauma horror summarized decades before the onslaught of lazy, hackneyed approaches

to the same treatment that currently scatter the horror film landscape.

7. Uppercase Print (2020) - "The perpetrator may live close by. Or they may live far away".

Taken

from transcripts of the Romanian Securitate as they investigated the

sudden appearance of chalk graffiti around the city in mid 1981, Radu

Jude's "Uppercase Print" is an intellectual examination of both a time

and place where liberty needed to be called upon as a dying idea.

Interspersing governmental films, weird musical interludes, and VHS

images of the country (complete with bad VCR tracking issues!) amid a

theatrical reading of the now released investigation notes of the

graffiti that eventually ruined the life of a young student, "Uppercase

Print" begins as a dryly humorous effort before shifting into an

especially acrid portrait of oppressive nationalism. The above quotation

is from the crack investigative reports of the secret police and Jude's

film initially seems like a comedy of communistic generality. It's clear the government's procedure is casting the widest net possible and mopping up anything they deem "anti-them". Needless

to say, things turn very dark, formally assured and completely

heartbreaking by the end. I haven't seen a few of Jude's other pointed

mixed-media documentaries about his home country, but after this one, I

look forward to diving into them.

(1975) - George Roy Hill's film about barnstormers in 20's middle America is an especially wise film beyond its 'scope aerial vistas and Robert Redford infused charm. It's also a film of two halves. The first deals with the chaotic gamesmanship between pilot Redford and fellow flyer Bo Svenson as they try and one-up each other in conducting aerial flight tricks for enraptured audiences. And even though they often end up bruised and battered, it doesn't stop their obsession with circus-like and envelope-pushing stunts. But the second half- after both men have been officially grounded due to some pretty horrific accidents to those close to them- "The Great Waldo Pepper" settles into a reflective conversation about men past their prime, re-living war glory, and their sublimated place in the early days of Hollywood stunt filmmaking. And when an ex-German war hero comes into the mix (played with subtle grace by Bo Brundin), Redford's Waldo Pepper morphs into a man reclaiming his past glories and daredevil fatalism in a finale that's both thrilling and melancholy for how it portrays these men who wish more to be martyrs in the sky rather than living as ordinary schlubs down below.

(1968) -

In a scene towards the end of Carlos Saura’s psychological chess match “Stress Is Three”, a man Antonio (Juan Luis Galiardo) is grounded, literally and figuratively, when he tries to drive away in his car on the beach and ends up only spinning its wheels in the sand. This comes after the frustration (and imagination?) of him seeing his wife (the luminous and blonde wigged Geraldine Chaplin) making out with their best friend Fernando (Fernado Cebrian) behind a jetee of rocks on the beach...... an act poor Antonio has internalized the entire film. It’s his breaking point, but in typical 1960’s ennui fashion, it's a violation of the human contract between husband and wife that may have only happened in his mind. If nothing else, Saura's film is about the disconsolate attitudes of the privileged and how they tear each other apart when left to their own devices. Taking place over the course of just a couple of days, the trio embark on a road trip together. There’s no denying the flirtation between Teresa and Fernando from the very beginning. It’s enough that at one point, Antonio sneaks off the road ahead of them and spies on them through his binoculars. And because this paranoid act occurs towards the beginning of the film, it's a nervously implied sequence that sets the ominous tone that something is happening.

4. The Enemy Below (1957) - A naval war film that excels because it humanizes both sides of the altercation. When we first meet the German submarine commander, played by Curd Jurgens, he's commiserating about the effects of war on humanity. Far from being a Fuhrer acolyte (his disdain is subtly reflected later when the man's name is mentioned by another soldier), "The Enemy Below" shares screen time between his desperate attempts to save his hunted German U boat and out maneuver the American hunter above, led by captain Robert Mitchum. Eschewing the usual patriot fervor that accompanies most of the big studio war films of the 50's, Dick Powell's muscular effort is all the better for how it equals both sides of the conflict as simply men who want to see all their subordinates return home in one piece. Directed with muscular flare by Dick Powell, the depth charge explosion scenes are worth the price of admission alone. War movies done right.

3. Alive In France (2017) - Two things are made incredibly clear in "Alive In France", Abel

Ferrara's documentary about his overseas promotional tour with his band

while attending a retrospective of his films; first, he scratches

together music with just as much abandon as he does film making. From

the way he pieces together various drummers in each city to how he

vigorously commands the light show at each club, Ferrara is an alpha

auteur in every sense. Secondly, the documentary fits perfectly with his

late career work of quieter, more reflexive pieces of cinema that act

as love letters to both the creative process and the people he's chosen

to align himself with. As he answers one patron in a Q&A session,

the New York of his older films doesn't exist anymore, so why should he

continue making films about gangsters? Well, "Alive In France" is still a

Ferrara film, beating with the hard-scrabbled heart of his previous

films but tinged with a sense of nostalgia and passion for his latest

role in life. It makes him immensely happy (despite the pressures of

performance) and it's a film that makes us incredibly happy as well. The documentary also continues the filmmaker's varied late career of submerging himself in a cerebral fictional film while seeming to release his pent up fictional ruminations with a loose and freewheeling work of non fiction.

2. Dusty and Sweets McGee (1971)

Honed into the type of leisurely, anemic snapshot-of-time that would

come to define the careers of Sofia Coppola and scores of others in the

post 90's indie new wave boom, Floyd Mutrux's "Dusty and Sweets McGee"

outlives its thin pseudo documentary beginning to morph into a sobering,

half-dreamt memory of sunny California and the dark storms of addiction

that roll just beneath its pleasant surface. That this film is

relatively unseen today (thank you Turner Classic Movies for its late

night broadcast this month!) only adds to the film's lilting presence

somewhere between tone poem beauty and after school special didactic. Beginning with introductions to its main slate of characters (supposedly

real addicts playing themselves), Mutrux lets the good times roll,

synching images of their late night car drives around the valley and

frolicking in bedrooms to a host of popular tunes as if timed to a

hay-wired jukebox unable to settle on 1 song for long. Even though it

feels like "American Graffiti" (1973) and Mutrux himself would later

direct "American Hot Wax" (1978), the film soon settles into the darker

reaches of its time and place as various young men and women go about their drug-addled days of dream-big heists and opium-dazed dalliances. Released briefly in 1971, "Dusty and Sweets McGee" never quite made the

mark it hoped. Although Mutrux is perhaps one of the more underrated

writers and filmmakers of the 70's, the film is one of those discoveries that needs to be made. It may seem

tame in comparison to the German miserablism of Uli Edel years later,

but as a touch point in independent American lyricism, its message hits

loud and clear.

1. The Garden (2005) - As usual, Wiseman makes a strong statement about class, society, and human theater without saying any real words of his own, choosing instead to cultivate images and juxtapose them in luminous ways. Filmed in the mid 90's and chronicling the various high profile events and mundane conventions Madison Square Garden plays host to, "The Garden" is infinitely more enlightening when it pivots away from the spectacle and observes the proletariat (cooks, security, ticket takers and floor crews) that really drives the engine of the landmark. Why is it more interesting to watch how cotton candy is made then the Bulls and Knicks playing a game? Why is the message of a self described cat masseur more intriguing than the anti-union discussion of Garden management staff? Because that's exactly what makes all Wiseman films so essential. He takes a single location or event and mines the tree rings for all its worth. And, if nothing else, the film confirms my belief that we humans are the most filthy thing on the planet by the mountain of trash and food that's swept into the aisles by the janitorial staff after an event. As our greatest living documentarian, Wiseman's deep vault efforts continue to fascinate and enlighten even when the subject matter seems like no amount of energy or new information can be gleaned from its antique halls.

No comments:

Post a Comment