itsamadmadblog

Wednesday, April 03, 2024

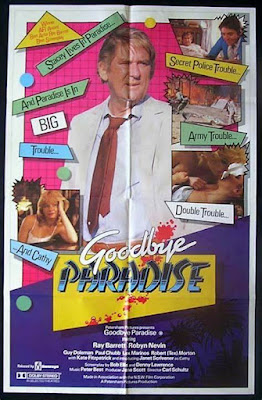

Camera Obscura: "Goodbye Paradise"

Saturday, March 02, 2024

The Current Cinema 24.1

Origin

In "Origin", Ava DuVernay takes a sweeping nonfiction book and not only manages to weave a heartfelt portrait of the author herself, but illuminate the thesis of the narrative with a magnificent, globe trotting vision. From Nazi-era Germany, to the Jim Crow infested American South, to the inhumane treatment of a certain sect of people in India, "Origin" almost becomes an overwhelming viewing experience for the way it plots Isabel Wilkinson's ideas about the caste system around the world while maintaining the emotional pull of a woman (Anjanue Ellis-Taylor) whose own personal life is spiraling towards grief. Sound, score, acting.... all the components merge here in what is probably DuVernay's finest work to date. Certain moments in "Origin" hit me so hard. It's a film whose sobering outlook on the subconscious manipulation of the world by certain power groups, at times, pales in comparison to the indominable spirit of those awake enough to fight back. One of the year's best.

Perfect Days

Wash. Rinse. Repeat. That's the rhythm Wim Wenders establishes in this peaceful, warm look at a janitor (Koji Yakusho) and his day-to-day routines. Those routines soon reveal tiny fissures (a manic co-worker and a visit from a family member), but "Perfect Days" fits solidly into Wenders' body of work. There are plenty of driving scenes timed to American rock 'n' roll and, even though the film takes place entirely in the city of Tokyo (which Wenders milks for all its florid beauty and concrete magic), the whole things still feels like a road movie. A few flourishes miss the mark (such as the appearance of a male figure towards the end of the film that seems shoehorned in to emit some schmaltzy magic realism), but overall "Perfect Days" is Wenders best film in some time.

Drive Away Dolls

If there's one thing the recent split of Joel and Ethan Coen has taught us, it's that each one certainly has a distinctive worldview that meshes their films into the audacious and compelling potpourri they've been delivering for more than 30 years now. Whereas Joel seems to be the more ponderous of the duo (i.e. probably where "A Serious Man", "Barton Fink" and "Inside Llewyn Davis" comes from) Ethan bends towards the cartoonish. And based on the humor and bawdy outlook given off by his "Drive Away Dolls", I'm tempted to say "Raising Arizona" is certainly all his. Alas, I still wasn't completely taken by "Drive Away Dolls" even though the laughs are dialed up to eleven and the tone swings wildly from scene to scene. Part of the problem are the two leads, played for all the gusto by the Texwas-twanged Margaret Qualley and the prim, buttoned Geraldine Viswanathan. As the latest in a string of Coen-esque protagonists on the lam and falling into various predicaments that ranges from the horny to the horrific, they feel like paper-thin representations of comedy. Add to it a tone that never quite finds its footing and "Drive Away Dolls" may be my most least liked Coen endeavor in quite some time. I do give it props for totally upending my expectations of just what exactly is in the briefcase, though.

Sunday, January 21, 2024

70's Bonanza: Martha Coolidge's "Not a Pretty Picture"

Swaying back and forth between fiction and documentary, "Not s Pretty Picture" is quite harrowing in either form. As a fictional film, the specter of dangerous seduction hovers at the edge of the frame. Young Martha (Manenti) is drawn into a double date with another girl where the two (alongside three men, including the eventual perpetrator played by James Carrington) end up in a dilapidated New York loft whose central feature is a hole in the wall that leads into another room where young Martha will eventually be victimized. If watching the act itself played out in long form isn't crushing enough, Coolidge shrewdly intercuts the various conversations, rationalizations, and conflicted attempts of the actors to contextualize their actions around her acted film. It's this debate that sets "Not a Pretty Picture" apart from other personal essay films. Coolidge doesn't shy away from the varying degrees of guilt and acceptance. Even if actor Cunningham gives some feeble attempts at his character's actions, Coolidge allows the space for everyone. It's awkward at times. Strikingly painful at others. And while not a necessarily healing experience (as the final few moments of emotion on Coolidge's face exemplify), the film definitely feels like a quiet scream of simple pronunciation about the act that Coolidge needed to explore. That alone is worth this film being seen by as many as possible.

Wednesday, January 17, 2024

My Favorite Films of 2023

The full list can be found here: My Favorite Films of 2023 | Dallas Film Now., which has basically transported the more professional writing I'm currently doing. I don't want to forget this humble home, however.

Tuesday, January 02, 2024

The Best Non 2023 Films I Saw in 2023

10. Bitter Innocence (1999) - Dominik Graf's "Bitter Innocence" twists about halfway through from a corporate thriller to a sweet love story borne out of the casual indifference and sexual violence men perpetrate on women. That the love forms between a twenty-something woman (Laura Tonke) and the young teen daughter (Mareike Lindenmeyer) trying to unravel the mystery her parents have immersed themselves in should come as no shock to those who've watched just a few of Graf's films. They are mostly love stories buried within a larger framework of genre. Last year's masterwork called "Fabian: Going to the Dogs" is one of the lushest romance film in years, buttressed against the backdrop of an encroaching Nazi evil. Situated firmly in the times it was made (1999), "Bitter Innocence" follows the same pattern as love is widdled out of the complicated yuppie mindset that those in the corporate world can get away with anything if their check book is large enough. But before we get to the central relationship of Vanessa and Eva, Graf's film wanders through the thriller realm when aggressive boss Larssen (Michael Mendle) threatens to destabilize the vague pharmaceutical company Andreas (Elmar Weppar) has been conducting research within for the past few years. Andreas' fears about the wolf Larssen are confirmed when he discovers him raping Vanessa behind closed doors. Working as a waitress for a catering company providing services at a company party, Andreas doesn't report (or even lift a finger to help) the vulnerable Vanessa, instead using the act to steal a file that may secure his employment..... which is a prickly move since Vanessa sees him dodge out without coming to any sort of chivalry rescue. With the visual style of a glistening television movie (Graf has careened through an array of features, both for the big and small screens) and a sense of rhythm like that of a soap opera, the film's themes of ravishing passions and high intrigue feel right at home with that lowbrow entertainment. But Graf's swirling ambition about the youth of the world being the most morally grounded figures in a world set on financial gain and personal advancement (and I didn't even mention the affairs!) fits right at home in the subversive tactics of a filmmaker who continually buries so much in his works. I look forward to carrying through with his expansive body of work.

Monday, November 06, 2023

The Current Cinema 23.5

Killers of the Flower Moon

Scorsese's latest is a corrosive epic that clearly reveals its shades of morality for everyone involved within the first third, then proceeds to deliberately track the insidious nature of violence and deluded companionship over the remaining three hours. Imagine if the walls closing in around Henry Hill in "Goodfellas" were protracted out for 180 minutes. That's the startling feeling that Scorsese manages to uphold in "Killers of the Flower Moon", but this time, the criminal activity mirrors that of the American mafia played out in the dustbowl setting on 1920's Oklahoma and the violence against the Osage Indian nation for their valuable oil land head rights. With his usual cast of heavyweights (DiCaprio and DeNiro), the biggest coup of the film goes to the steely beating heart of Lily Gladstone as "Killers of the Flower Moon" was changed from its FBI-instigated criminal investigative tone to a more Native-American centric point of view. It works wonders, no less because of the stellar, granite-faced supporting cast and a rhythmic editing style that constantly makes one gasp with horror at the nonchalant violence and overhead writhes of death encompassing the entire land. Like he's done for New York, Las Vegas, and even the bashing waters off a Japanese prisoner colony, Scorsese spiritually imbues nature with a fist of violence that's hard to shake.

Anatomy of a Fall

Justine Triet's masterful, slow examination of a death also places on trial the ebbs and flows of a marriage.... where every charged conversation is a motive for murder and perception shifts between parties wildly. Sandra Huller is the woman on trial after her husband's body is found outside the window of their three-story, snow-capped mountain chateau. Is it suicide, murder, or a simple accident? And like the best films that work in gradual shades of morality, "Anatomy of a Fall" is less concerned with what really happened than the verbal gymnastics and hidden emotions that might have led to all this. Employing a camera that's often trying to follow what's happening just as quickly as the audience (i.e. that startling whip pan when Huller's son is announced as a witness) and brilliant performances from all involved, "Anatomy of a Fall" is two-and-a-half hours of French courtroom politics trying to decode matters of the heart. It's dry, intelligent, and ultimately so haunting.

Priscilla

Sofia Coppola's best film since "Lost in Translation", "Priscilla" is a film that continues on with the filmmaker's fascination with interiority and impressionism. It's also a drastically (and wonderfully) different experience from last year's Baz Luhrman sonic fest about Elvis Presly. As Priscilla Presly, newcomer Cailee Spaeny embodies the love interest of a rock and roll icon with her own sense of permanent dislocation in one of two scenarios- either orbiting the yes-man-good-ol-boy universe of Elvis' lavishly repercussion-free dalliances, or quietly within the controlled alienation from Elvis himself. This is made clear when Priscilla first sits down to eat with the protracted Elvis family, filmed in profile by herself, dutifully nodding to others outside the frame. There's not much room for else, and Coppola deftly alternates between these two environments, peppered with heart-stopping needle drops and a keen awareness of the objects and textures that suffocatingly surround Priscilla. In fact, the best description I can provide of "Pricilla" is a film of quiet suffocation, made all the more enervating when the finale happens. It's no secret Elvis was a victim of explosive stardom, but at least someone survives this sinkhole universe of carnivorous public consumption. And a Dolly Parton needle drop is the perfect way to frame Priscilla's flight to freedom.

Monday, August 28, 2023

The Current Cinema 23.4

Passages

It'd be misleading to read Ira Sachs' latest effort, "Passages", through the eyes of its amorous, confused, and ultimately destructive lead character Tomas (Franz Rogowski). Oscillating between the relationship with his husband, Martin (a tremendous Ben Whishaw who deserves all the year end accolades) and his start-up affair with beautiful teacher Agathe (Adele Exarchopoulos), Tomas doesn't feel that far removed from the caddish interlopers of the French New Wave. But "Passages", ultimately, concerns itself less with Tomas and more with the two people caught up in his sexual confusion. This is a film about frank sexuality- which is terrific when it's fresh and impetuous- and all three people in this love triangle experience it. However, what lingers most vividly about the situation is the way Sachs quickly dries out the sexuality and creates a devastating portrait of those rejected and damaged from Tomas' willful carnality. Whishaw is brilliant in the way he recoils and holds in his sadness during one incredible scene. Likewise, Exarchopoulos is luminous in her stringent performance and the way she maintains a sense of individuality within yet another expression of amour fou (something she's become famous for). I suppose all the character traits were there on display in the opening scene as filmmaker Tomas berates and constantly stops a scene he's filming in order to get the right presence of someone walking down a flight of stairs. "Passages" is an exploration of the starts-and-stops we experience in a relationship as well. It's just a shame it comes at the expense of two wonderful people like Martin and Agathe, who Sachs handles with empathy and intelligence.

The Last Voyage of the Demeter

Typically a dumping ground for left-over gambles and small independent films that finally manage to squeeze their way onto one of the 24 screen multiplexes, August is a miserable month. Add to that at least one horror film each year in a vain attempt at counter-programming, and that's where Andre Ovredal's "The Last Voyage of the Demeter" lands. Literally ripped from the pages of Bram Stoker's "Dracula" tale, "The Last Voyage of the Demeter" actually succeeds because of its swallowing atmosphere and confident bloodletting in a confined space. The space is a ship whose unlucky cargo happens to be the prince of darkness, and the cast is a who's-who of familiar character actor faces (Liam Cunningham from "Game of Thrones", Corey Hawkin, Aisling Franciosi, and David Dastmalchian) charged with battling the creature. There are no great revolutions here. It isn't saying much. The scares are generally rote. But what "The Last Voyage of the Demeter" does have is terrific production design and a suffocating sense of foggy, inevitable bloodshed. For the August dumping ground, that's enough for me to purely enjoy this film for what it is.

The Unknown Country

I love, love, love this type of wispy travelogue film that says nothing, but manages to say everything. As the woman traveling, Lily Gladstone deserves her big year, and Morrisa Maltz's "The Unknown Country" understands that the most powerful expression in cinema is not the words, but the face. Harboring a restless sense of sadness and displacement, the film follows Tana (Gladstone) as she travels from Minneapolis to her cousin's wedding on the reservation in South Dakota. From there, she heads south in search of something greater than herself. Generally keeping the viewer imbalanced on just where we are in the journey with Tana across an American landscape that's alternatively beautiful and alarming for a single woman, "The Unknown Country" also takes the time to dwell on the genuine, honest faces Tana comes across in her journey. We even get to hear these people tell a quick story of their lives, and a fiction film becomes semi-documentary... as if Maltz also wants to craft an anthropological study of the goodness buried in a world teeming with angry talk radio and the division of people- something that becomes central to Tana's long car rides that not only serve as a location marker, but also the static of a world going on carelessly around her. Ultimately, "The Unknown Country" knocks all this away and chooses to emphasize the people orbiting around Tana. Best when it settles on the sweet, proud worldview of her estranged relatives on the Indian reservation (including a knock out performance by long time character actor Richard Ray Whitman), it's enervating to watch Gladstone's performance begin to soak in their grace and carry on southward for something more. The world may still be swerving around her, but "The Unknown Country" has the grace and fragility to slow everything down and celebrate those in the moment. A wonderful film.

.jpg)